|

This text

is dedicated

to all of you PrefaceThis document, now called Arch 101, is the web version of a guide I wrote years ago to help some friends interested in Linux get an easier onboarding. The style is informal, but I think the information can still be useful for newcomers, so I decided to upload it here. "Arch 101", previously named “Introduction to Arch Linux”, and “Arch Linux Installation & Configuration” before that, is the result of two colliding forces: The first one, an effort to gather and compile meaningful documentation about the installation, configuration and architecture of Arch Linux in order to have a handy, yet old-school, manual to use as reference (initially for me and for my friends). The second one, that I wanted to consolidate my Linux knowledge and also learn anything that came across while writing this. Computers are incredibly fun and learning how they work is always an amazing experience. Writing and creating is something that brings me joy, and things that are done with love and joy will always be worth. For any questions on how any of this works, how to install or configure Arch please reach out to the official forums—or even better—read the wiki: it's extremely extensive and will (most likely) answer all of your questions. For anything regarding free software or third-party configurations, you can ask on the usual forums (stack exchange, etc.). Still, if you really want to get in touch with me personally, you can use the channels mentioned in the main page of this website.

As a final note, “unfortunately” (and I say unfortunately because the easier something gets for the user, the less you'll get to know how it really works) the Arch installation process has been simplified to an extent where a guide for it is not necessary, so anyone can easily get it running. Bragging about your anime-themed i3wm configuration is not as cool as it was 10 years ago. Still, I believe that documenting anything you do is a great way to settle knowledge (and I find it very entertaining), so I will try to cover as many aspects of Arch installation and configuration as I can while explaining all the background knowledge necessary to understand the main guide. 1. Setting upBefore we get down to business to defeat the Huns, we need to ask ourselves the following: Do I want to install Arch Linux? If you don't know the answer right away, let me help you. Perhaps if any of the following apply, you might want to consider switching to—or try—Arch:

If any of the above resonate with you, I'd strongly suggest giving (Arch) Linux a try. 1.1. Base knowledgeWhile the installation guide is intended for absolute beginners, you will need some background on a few key concepts that I will mention through the document. Since I also want this document to be self-contained, I will answer the top 10 most common related questions right now so we can have a common starting point from which we can build the rest of the knowledge. What's Arch Linux?Quoting the wiki: Arch Linux is a x86_64 general-purpose GNU/Linux distribution that strives to provide the latest stable versions of most software by following a rolling-release model. So we can define Arch Linux as a general-purpose GNU/Linux distribution for x86_64 systems which intends to provide the latest version of its software by using a rolling-release model. x86_64? General-purpose? GNU? Rolling release? What are you talking about? Alright, if it's the first time you've heard of these concepts I get it can be a bit confusing. For now, there's no need to explain each in detail, but let's make sure you have a basic grasp of what the concepts mean before you continue. For this, let me break them down for you: X86_64, also called X64 (or x64) or AMD64 (because AMD released the first x64 processor) refers to a family type of Instruction Set Architecture (ISA), commonly referred to as computer architecture. The ISA specifies the structure and behavior of machine code (a language that computers are able to understand). The ISA defines how the CPU should be controlled by the software, specifying both what the processor is capable of doing as well as how it gets done. So what does this mean? Essentially, that every set of instructions (you can understand it as a package of commands) we send to the computer in order to, well, compute, contains 64-bit of data. Let's take it as if a x64 PC was a post office and that every package has to weigh 64-bits. As a fun fact, nowadays x86-64 processors do not actually use 64-bit instructions but 48-bit instead. If you want to know more about this you can look it up on the Internet ;) General-purpose means that the Operating System was not developed with a specific use in mind and therefore can run many kinds of applications. While there are some OSes that are developed to run some specific software or under specific conditions, Arch, similar to Windows and MacOS, is a general-purpose OS that can be configured to meet the needs of its user. The GNU project is an extensive collection of free software that can be used as an operating system, or in parts with other operating systems. Operating systems that use the GNU packages (software) constitute what's commonly referred to as a GNU operating system. Rolling release is a concept in software development that consists of continuous delivery of software updates to applications. In practice, this means that Arch, unlike Windows and other OSes that have many versions, e.g. Windows 8, Windows 10, Windows 11 etc. and have to be re-installed or completely updated at a point in time, is updated at any given point by performing maintenance to the system and updating it, similar to any other usual desktop application.

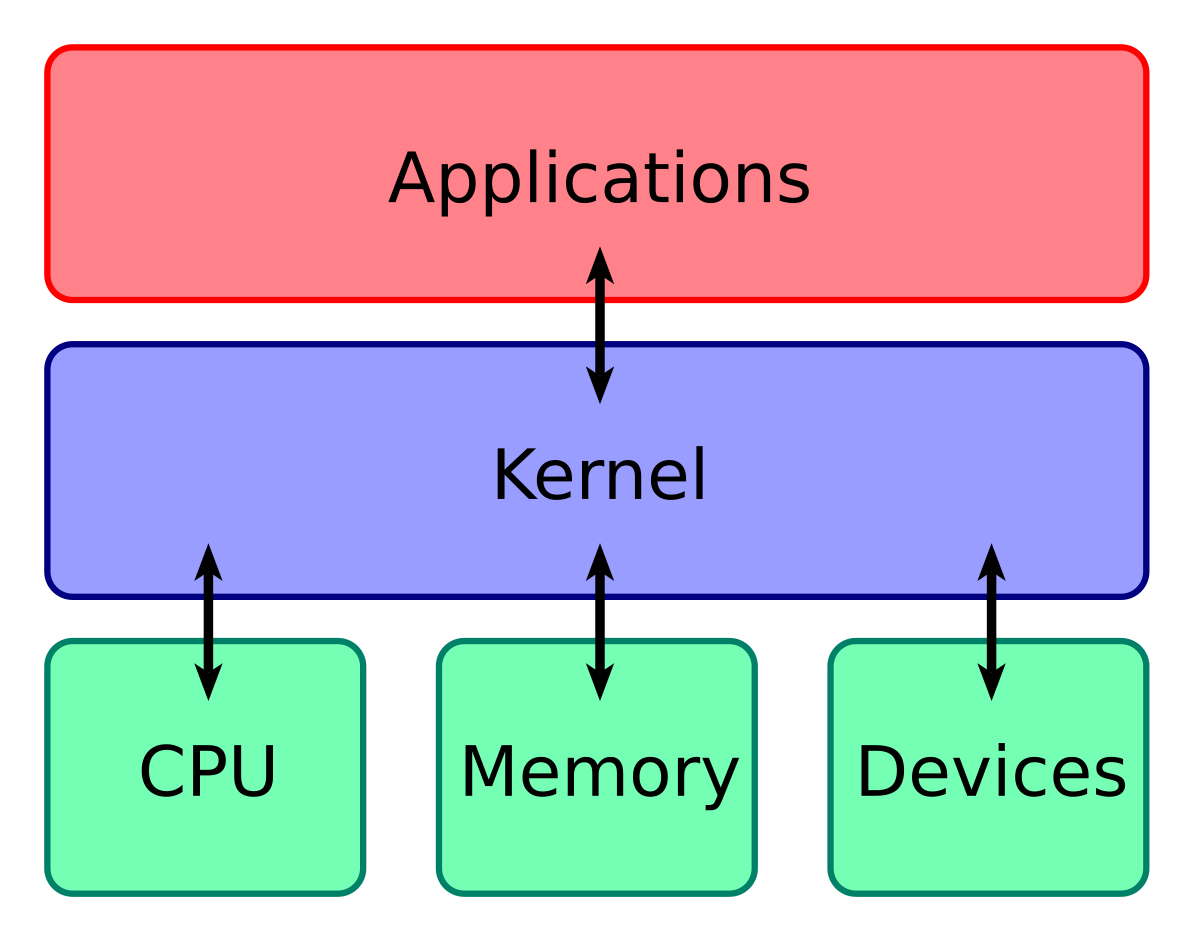

This meme pokes fun at the nature of rolling-release systems like Arch. The command Of course, not every Linux distribution is "bleeding edge", and there are more "stable" distros, but we'll get to it later. In any case, you now have more knowledge about Operating Systems than the average Joe. Before you get to deepen your knowledge or try to understand what you just learned, I'd suggest you go to 4chan /g/, MyDigitalLife, IT subreddit or whatever forum/board you find first and brag about how much you know about GNU/Linux. Trust me, this is a crucial part of the learning process. If you think you are not ready to brag on the Internet about your hacker knowledge, then let's try to give you more context on what we are going to study. We just learned that Arch is a “GNU/Linux” operating system, and I explained what GNU is. Therefore, the question that naturally comes to mind is: What's Linux then?Well, technically Linux is a kernel. To be more concise, a free and open-source, monolithic, modular, multitasking, Unix-like operating system kernel. There's no need to worry about what all of this means, these are concepts that we'll discuss later on as most of them are fairly complex. What's a kernel? Why are there so many concepts? For now bear with me, once you read all the concepts you will see how all of them are tightly related and that fully understanding one of them helps you understand the ones you don't fully understand yet. The kernel is the main component of an Operating System and is the central interface between a computer's hardware and software. To illustrate it here's an over-abstracted representation:

The kernel has 4 main jobs: The kernel, if implemented properly, is invisible to the user, working in its own little world known as kernel space, where it allocates memory and keeps track of where everything is stored. What the user sees (like web browsers and files) are known as the user space. These applications interact with the kernel through a system call interface (SCI). Think about it like this: The kernel is a busy personal assistant for a powerful executive (the hardware). It's the assistant's job to relay messages and requests (processes) from employees and the public (users) to the executive, to remember what is stored where (memory), and to determine who has access to the executive at any given time and for how long. That sounds like a lot. Where does the kernel fit within the rest of the OS? To understand this, let's separate the parts of a computer in 3 layers: The hardware: The physical machine. The bottom or base of the system, made up of memory (RAM) and the processor or central processing unit (CPU), as well as input/output (I/O) devices such as storage, networking, and graphics. The CPU performs computations and reads from, and writes to, memory. Looks like the kernel does everything or almost everything. What's missing? This is an interesting question. We could theoretically boot only the kernel (with a bootloader). However, nothing would happen because we cannot communicate with the kernel directly. While the kernel indeed is responsible for most of the operations between hardware and software, the concept “Operating System” is an abstraction. What we commonly refer to as an “Operating System” is just a group of applications sitting on top of the kernel that allows us (human users) to interact with the computer (and therefore with the kernel too). Did you just realize something? The “group of applications sitting on top of the kernel” is indeed what we previously referred to as “The GNU Operating System”. We are now running a set of free software components (GNU) on top of a free software kernel (Linux). GNU+Linux = GNU/Linux.

We are starting to understand what all of this is about! What's “Free software”?Unfortunately, if you search “free software” in a browser, you will get software that's “free” as in “free beer”. However, when we talk about “free software” we refer to software that is “free as in freedom” or, as the more modern comparison says, “free as in free speech”. The issue—like many things in this world—is caused due to the foul English language. The word “free” has two main meanings: “at no monetary cost” (gratis) and “with little or no restriction” (libre).Therefore, when I say “free” software I refer to libre software. What does this mean? How can software be free as in freedom? This is a very old and extensive debate that we can track back to the '70s. More formally, Richard Stallman (aka RMS) founded the “Free software movement” in 1983 by launching the GNU Project. RMS later established the Free Software Foundation in 1985 to support the project. In short, the philosophy of the movement is that the use of computers should not lead to people being prevented from cooperating with each other. In practice, this means rejecting proprietary software, which imposes restrictions on the user and promoting free software, with the ultimate goal of “liberating” everyone in cyberspace. As you might know, proprietary software comes with different copyright and distribution limitations that hinder the user's ability to obtain, modify and share it. By forcing the user to comply with each company's proprietary standards it prevents users from working together while corporations push their own products for revenue, since proprietary software also tends to be payment-based. Due to the inherent nature of proprietary software, some companies end up owning most of the market share for a particular product or service and abusing malicious practices like product price inflation and planned obsolescence, thus creating an oligarchy. Does Windows use Linux?No. The Windows family of Operating Systems does not use the Linux kernel. The modern Windows versions (from Windows NT to 11) use the Windows NT kernel, which—like the Windows Operating System—is proprietary. However, Windows can run an instance of Linux since 2016 with the help of the Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL). This allows Windows users to run a Linux environment without the need for a separate virtual machine or dual booting your system. This does not mean that the Windows Operating System uses the Linux kernel; Just that it can run by virtualizing it. Previously, Windows 9x (95, 98 etc.) used a basic code similar to MS-DOS. This one is a 16-/32-bit hybrid and requires support from MS-DOS to operate, and unlike Linux, is not based on UNIX (well, there's Xenix, but Microsoft decided to move away from UNIX in 1982). What the hell is UNIX?If you are not interested in computer history, you can probably skip this part. Still, I strongly suggest you read it as understanding the path from which we come from helps us to understand why things are as they are nowadays. UNIX is an operating system originally developed in the late 1960s at Bell Labs by Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie (yes, the creator of the C programming language) and a bunch of other insanely smart people. The idea was to create a multi-user, multitasking system that was portable across different machines (which was groundbreaking at the time). It also pioneered a lot of concepts we take for granted today, like hierarchical file systems, treating hardware as files, and the infamous philosophy of "do one thing and do it well". The original UNIX was proprietary, but its design and source code influenced a whole family of operating systems over the decades. This includes BSD (Berkeley Software Distribution), Solaris, AIX, HP-UX and, indirectly, Linux. While Linux is not UNIX (it was written from scratch by Linus Torvalds in 1991), it's considered Unix-like because it behaves and looks like UNIX from a user and programming perspective. Why does this matter? Because understanding UNIX's design helps you understand why GNU/Linux systems are structured the way they are. Commands like So, in short: UNIX is the spiritual (and in many cases literal) parent of modern operating systems, and Linux is one of its many children, albeit adopted. Knowing this heritage will make a lot of the design choices in Linux make sense. Wait, isn't Mac OS the same as Linux?Nope. While macOS and Linux look similar if you're just glancing at a terminal window, under the hood they are very different. macOS is built on a UNIX-certified core called Darwin, which itself is based on BSD (a direct descendant of UNIX) combined with components from NeXTSTEP (Steve Jobs' other OS project before he came back to Apple). So yes, macOS is literally a UNIX operating system, not just "Unix-like" like Linux. This is why a lot of the same shell commands you know from Linux will work on macOS, and why developers often say it feels familiar. However, as I said before, Linux is not derived from UNIX or BSD; it was written from scratch by Linus Torvalds in 1991, with GNU tools and utilities layered on top. The similarity comes from both following the same UNIX design philosophy, but their codebases and licenses are completely separate. Here's a simple way to think of it: macOS and Linux speak the same "UNIX language", but they have totally different DNA. One comes from the original UNIX family tree, the other is an independently created cousin that happens to share the same culture and habits. Why should I use (Arch) Linux over (Current proprietary OS)?This is the part where some people will expect me to say something like 'Because freedom!' or 'Because it's better!'. The truth is, it depends entirely on what you want from your computer. If you just need a machine to browse, watch videos and occasionally write a document, you can stick to whatever OS you have. Just say that you don't care about privacy or freedom on the Internet. But for me, it boils down to three things:

On top of that, Arch Linux gives you:

If you want a machine that works exactly the way you want, respects your privacy, and keeps you in control, Arch Linux is an excellent choice. If you prefer an OS that hides everything behind wizards and makes all the decisions for you, stick with whatever came pre-installed on your laptop. Is Linux used?Yes. Everywhere, even if you don't see it. Linux runs most of the servers that power the internet, the majority of supercomputers, Android phones, smart devices, routers, and more. It's behind most cloud infrastructure, powers the systems of big tech companies, and is heavily used in scientific research, finance, and entertainment. If you think Linux is 'niche', it's only on the desktop where it's less common. In short, if you used the internet today, you used Linux. Why are there so many Linux distributions?Because Linux is free and open source, anyone can take the source code, modify it, and release their own version. Over the decades, this has led to hundreds of distributions (or "distros"), each tailored to different needs. From beginner-friendly systems like Ubuntu, to minimal, do-it-yourself distros like Arch, to highly specialized ones for servers, security testing, or even running on tiny embedded devices. Some distros exist to provide a particular desktop environment or workflow, some aim for maximum stability, while others focus on bleeding-edge updates. The abundance of choice is a double-edged sword: it can be overwhelming at first, but it also means you can find (or build) a Linux that fits you perfectly. That's the official statement though. In my opinion, just like the left, freedom advocates (i.e. distro makers) tend to disagree on stupid things. Everyone wants their own flavor of "the right way" to do Linux, which results in fragmentation instead of unity. That's why I think the Linux desktop will never truly flourish in the mainstream. Not because it's technically inferior, but because the community can't agree on a single path forward. What's BASH?BASH stands for "Bourne Again Shell". It's a command-line shell and scripting language that serves as one of the most common ways to interact with a GNU/Linux system. When you open a terminal and start typing commands, you're usually talking to BASH (unless your system uses another shell like Zsh or Fish). A shell is basically a middleman between you and the operating system's kernel. You type a command, the shell interprets it, and then it tells the system what to do. BASH is particularly powerful because it supports scripting, meaning you can automate tasks by writing them in a text file and running them whenever you want. BASH has been the default shell for most Linux distributions for decades. Even though there are other shells out there, knowing your way around BASH is practically a rite of passage for any Linux user. It's like learning to drive stick shift; maybe not strictly necessary anymore, but it gives you a lot more control. 1.2 PrerequisitesIn order to install Arch we'll need the following:

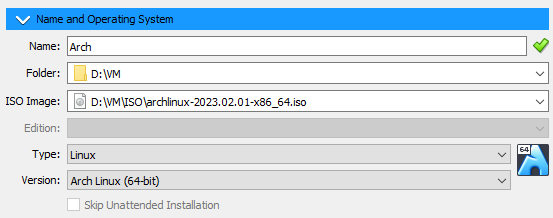

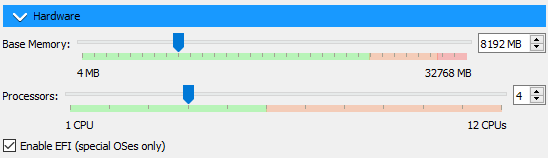

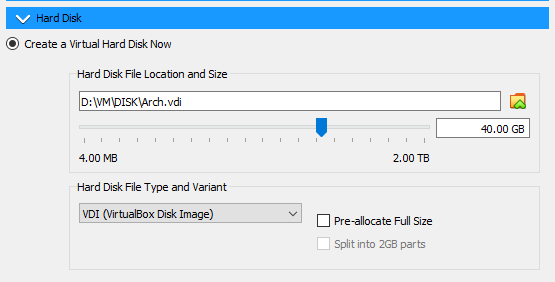

With the above, the Arch wiki recommends first to verify the signature of the ISO. After this optional step (or if it was omitted), prepare an installation medium, e.g. use Rufus or Win32diskimager to create a bootable USB with the Arch ISO. I will use VirtualBox for most of the installation and configuration, except when showing WiFi configuration by using a laptop. 1.3 Pre-InstallationThis is the setup I will be using. I'll explain each setting so you can mirror my VM settings.

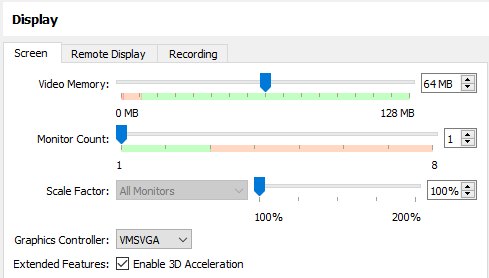

Video Memory: 64 MB will suffice for our desktop environment.

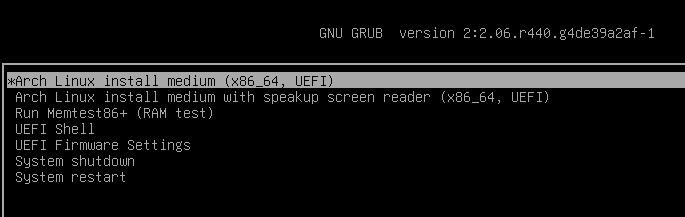

InstallationWith my settings you should be able to boot the machine. If you are using a Virtual Machine, remember to enable virtualization for your host (this is changed in the BIOS. If you don't know what any of this means just search “Enable virtualization” on the Internet and follow the steps there). If you are using a physical computer, you should only care about meeting the requirements listed above (and having a UEFI-compatible device, which in the current year shouldn't be a problem unless you're using a refurbished old system). If your settings are correct, after loading whatever media you have with the Arch ISO you should see something like this:

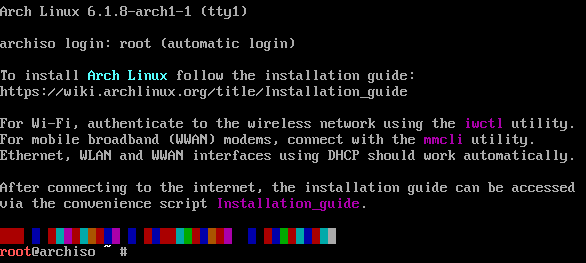

Let's select the first option “Arch Linux install medium (x86_64, UEFI). After loading you should see the following prompt:

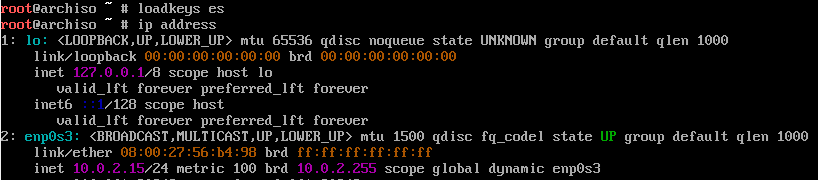

Note: From now one you'll see commands, you have to enter what's after the "#". Let's load our keyboard layout, the default one is the US keyboard. In my case, I'll use the Spanish layout “es”, for this enter the command: After this, let's ensure that we have an Internet connection by checking our IP address and performing a ping to a web on the Internet. (If you are using a NAT connection on VirtualBox you should see a Class-A IP (10.0.2.15), if you are using a Bridge Adapter or a physical device, you should have a Class-C IP (e.g. 192.168.1.10):

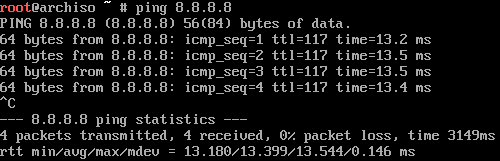

Let's now ping an IP on the Internet to see if we get a response, let's ping Google (8.8.8.8) with:

If you don't get a response (e.g. it says that the request timed out or the host is unreachable), double-check your interface and IP, try to ping another site etc. Using WiFi? Click hereIf you are using WiFi, use the iwd utility to connect to your network. Just follow these steps: First, start the tool: Within iwd, you can get a "device" list (i.e. your network adapter) that will allow you to connect to the network: Usually it's something like wlan0 (we'll assume this is the case, but you can swap "wlan0" with whatever you get). Now make sure the adapter is on: Then scan all the networks it can reach: You will not get any feedback from that, so in order to get what your adapter just got let's enter this command: And finally, let's connect to our network. Put the SSID (name) and the password: Now that we ensured that we have an available Internet connection, we need some final checks: First, make sure that we are using UEFI, to do this run the command: If the output doesn't tell you the directory doesn't exists, it should return something like this:

In the case the directory doesn't exist but you know your PC is using UEFI, make sure you booted in UEFI mode. Okay, we are now ready to install Arch. However, we are not going to use the standard method. Instead, we are going to use a command line utility that was created to speed-up and ease the installation of Arch Linux without needing to manually set everything up by yourself. For this, run: If everything goes OK, you should see something like this:

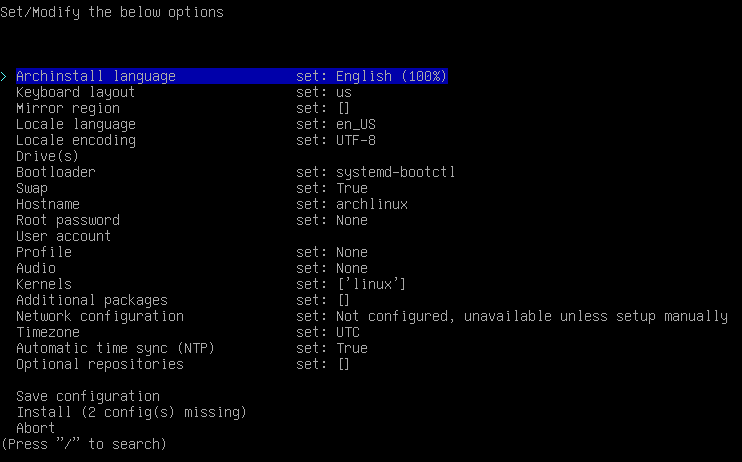

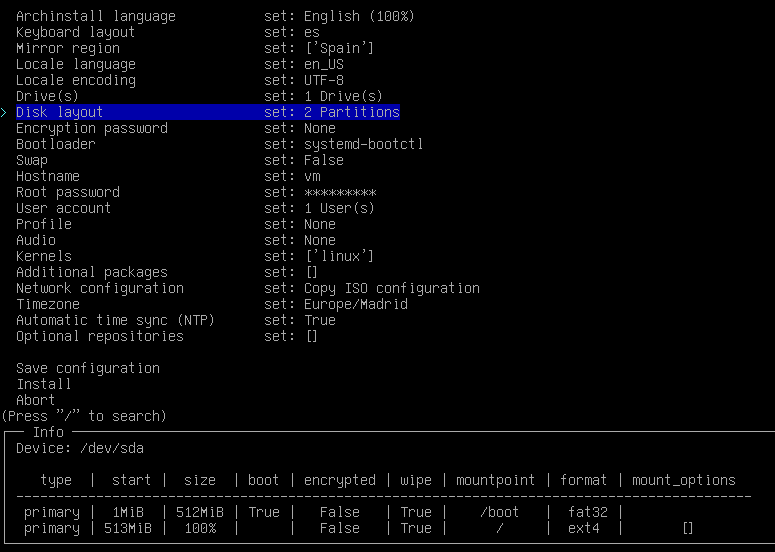

Some people might tell you are less h4x0r for taking a “shortcut”. Do not listen to them; archinstall is a command provided in the Arch base package and therefore is “as Arch” as pacman (the package manager used by Arch). Anyway, this is very easy: Simply go through each parameter and press Enter to configure. Here you have a peek of my settings:

Most settings are self-explainatory, but I will explain the ones you might not be familiar with:

And they said installing Arch was hard! Post-InstallationAfter rebooting, make sure that Arch starts, you can log in and that you can access the Internet. Maybe in the future I will make a rice guide for Arch. But for now you can stick to installing the usual software (web browser, text editor, etc.), and popular desktop environments.

|